Many of us follow a similar flow-chart when choosing a bottle of wine. We may start with the color, style and varietal before zeroing in on the labels, all while hovering around a comfortable price point. Familiar names stand out, as do pretty and cleverly designed labels. But, are we missing key information?

We took a deep-dive into decoding wine labels with the help of Erin Troxell Schorran of Galen Glen in the Lehigh Valley AVA. She shared easy ways to “read” the data on all parts of the wine bottle to make an excellent choice, every time.

An Overview

There are typically two label parts on a wine bottle: the front and the back. The front label carries the “who, what, when and where” information, while the back gets into more details and mandatory messaging. Sometimes, a winery will fit everything on one front-facing label.

There are certain elements of the wine label that are legally required by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB), and others that are optional. Wines sold through state stores and distributors must have labels registered with the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB). Wines produced and sold exclusively on-site, like at limited wineries, are sometime exempt or heed less stringent state-level requirements.

The labels, themselves, are typically made of paper or synthetic film with adhesive on the back, like big, pressure-sensitive stickers. Smaller wineries, like many of those in Pennsylvania, often order their labels from a printing company, like Graphics Universal in Greencastle, Apogee Industries in West Chester, McCourt Label in Lewis Run and Topflight in Glen Rock.

Paper labels might be matte, gloss or even textured, embossed or foiled. Sparkling and chilled wines require the water resistance of a synthetic label or protective-coated paper to withstand condensation.

A winery’s label design might be created by in-house staff or an outside freelance designer or branding agency. Galen Glen currently has four distinct label designs for its Galen Glen, Erin Elizabeth, Landscape Collection and Sip in Sin series, each reflecting the personality and story of those portfolios. For example, the primary Galen Glen label design looks like a molecule, a nod to owner and winemaker Sarah Troxell’s background in chemistry. The Erin Elizabeth labels are minimal and elegant, with a small, foil molecule icon above black script on a light background, in line with the spirit of these premier sparkling wines that allow the terroir to speak for itself.

Reading the Front of a Wine Label

Facing you from the shelf, the front of a wine bottle carries valuable information. Some of it is required by law, and always present. Other data points are shared by choice.

Brand Name: On every bottle of wine, you’ll see the wine’s brand name, frequently at or near the top in large lettering. This is often, but not always, the name of the winery. When it’s the same, that “estate-model branding” puts forth a unified vineyard and commercial identity and sense of place. Many Pennsylvania wineries, including Waltz Vineyards, Penns Woods and Nissley Vineyards, use this model.

Other times, the brand and producer names differ, such as with Mazza’s The Perfect Rosé, produced by Mazza Vineyards. In cases like this, a larger winery may choose to establish and market various sub-brand identities. The brand and producer might also differ if a corporation, like Trader Joe’s, owns a private label brand of wine produced by other entities, or if a winery produces a “custom crush” for an outside brand or winemaker.

When the brand and producer differ, the producer name is typically found on the back of the bottle following wording like “Produce and Bottled by…” or “Cellared and Bottled by…”

Wine Type or Variety: What’s inside the bottle? You’ll find that listed clearly on the front label of every bottle of wine, though not always in the same way.

Following TTB regulations, every bottle must list either the class of wine or, more specifically, the varietal or if it’s a blend. The list of class types is long and include commonly used terms like table wine, dessert wine and red, rosé, pink, white and amber wine. It also includes mead and cider, frequently produced in Pennsylvania, and classes connected to other countries such as Burgundy (France) and Porto (Portugal).

Wineries can also simply list “blend” or something like “dry red blend” on the label, indicating that multiple grape varieties were combined for the wine. If the winery wishes to name the specific varieties within the blend, like Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon, or different fruits, it must list the percentage of each one.

Wineries can (and frequently do) opt to be more specific and list varietals, or grapes, like Riesling, Chardonnay, Chambourcin or Cabernet Franc. If you see a varietal listed on a wine label, you know that 75% or more of that wine is from that grape. If listing a varietal, the winery must also include the region, whether state, county or American Viticultural Area (AVA), which we’ll get to in a moment.

Alcohol Content: The wine’s alcohol by volume (ABV) is listed on all bottles. It’s a number that’s not always as straightforward as it may seem, representing a range and, for some palates, holding insight into the wine’s character.

Wine ABVs fall into two categories for federal tax purposes. The first is the 7% -14% ABV range, with a margin of 1.5%. For wines in this category, the label must either state the exact ABV or say “table wine.” The second category the 14-24% ABV range with a variable of 1%. Wines in that range are federally classified as “dessert wines” and must list the ABV on the label.

Schorran explains that someone with a discerning palate might notice a wine’s ABV as they drink it. “With dry wine, you can taste a difference even when you’re talking about half a percent,” she says.”In states like Pennsylvania, it can be a good indicator of ripeness. If you see a little bit higher of alcohol content, it most likely means the grapes were a little bit more ripe that year and might be from a better vintage.”

However, the ABV margin can really skew the data. A wine labeled as 12.5% ABV could have as much as 14% or as little as 11% ABV. As Schorran says, “That’s a huge range.”

Net Content: All wine bottles must state how much liquid is inside, using metric units terms. The vast majority of wine bottles hold 750 milliliters (mL), about five glasses. On the larger side, a magnum holds 1.5 liters, about 10 glasses and a jeroboam holds about 20 glasses at 3 liters. The smallest bottle is a split, which contains just one glass in a 187.5 mL bottle.

Region/Appellation: Many, but certainly not all, wine labels state the location where the grapes were grown. This is separate from where the wine was bottled, which is not listed. As stated previously, appellation of origin is required on all bottles specifying a grape varietal.

If a winery is located within an AVA, you’ll likely see that listed on the bottle, signifying the unique qualities of that terroir. Otherwise, you might see the state or county listed. If you see a county, state or country listed on a label, 75% of the grapes were finished there. To list an AVA, 85% of the grapes must be finished in that region. To list a vineyard, 95% of the grapes must have finished there, and an “estate grown,” or “estate bottled” wine uses 100% of grapes from the vineyard within the same AVA as the winery.

Estate bottled wine with the AVA listed

Interestingly, winemakers can use other states’ appellations of origin if that state borders its own. For example, a Pennsylvania winemaker could create a wine with New York-grown grapes with “New York” listed on the bottle, since the states share a border. However, as Schorran explains, “I can’t buy grapes from Washington state and have them trucked across the country here to Galen Glen and then label the wine as ‘Yakima Valley’ wine. I would have to label it as “American.’” This regulation helps growing regions to retain their earned identities and reputations.

Vintage: A wine’s vintage is the year the grapes were harvested. This information is not required, but very valuable.

In Pennsylvania, Schorran says, “It’s not out yet, but 2024 was the best vintage we’ve had in 30 years of making wine at Galen Glen. The growing season was unbelievably cooperative. There was beautiful fruit across the entire Northeast.”

As we wait for that vintage, let’s keep an eye out for 2019, 2020 and 2022 Pennsylvania vintages, which Shorran also notes as “strong years.”

As for vintage expirations, Schorran says, “In general, our recommendation for most sweet white wines and wines with residual sugar is to consume them within the first two years. Some white varieties like Riesling and Chardonnay and dry red wines from a good vintage can age 10-plus years. And, late harvest products like ice wine, port and dessert wines are suitable for long-term aging.

Certifications: Often a challenge to achieve, certifications can be a point of pride for wineries to include on their labels. These include USDA Organic, Made with Organic Grapes, Demeter Biodynamic and SIP or LIVE-Certified, which you might see on the front or back of the bottle. Keep your eyes out for these terms to pop up on Pennsylvania wine labels as such certifications become more accessible and widespread.

Behind the Scenes

On the back of a wine bottle, you’ll find a few more key data points.

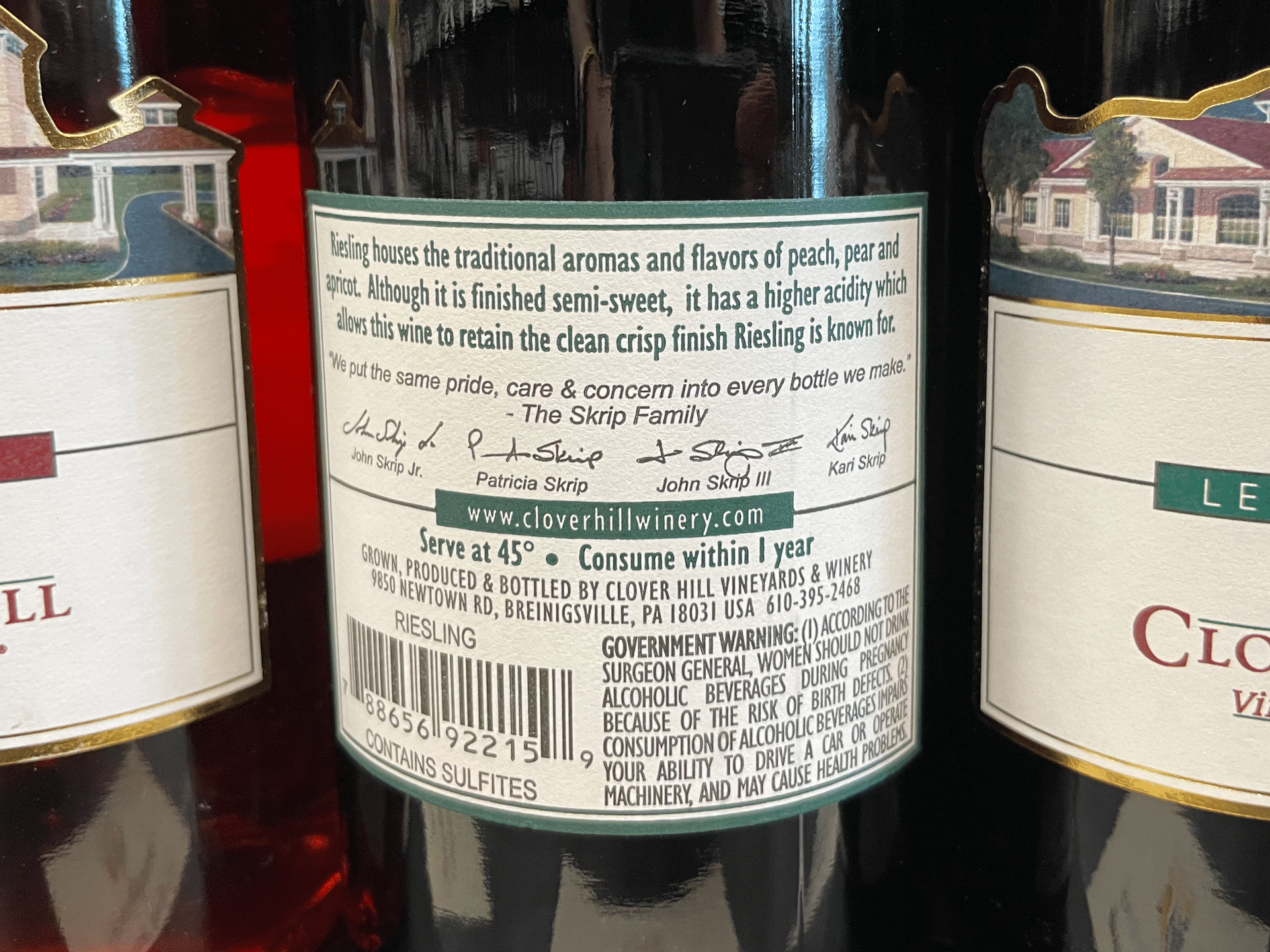

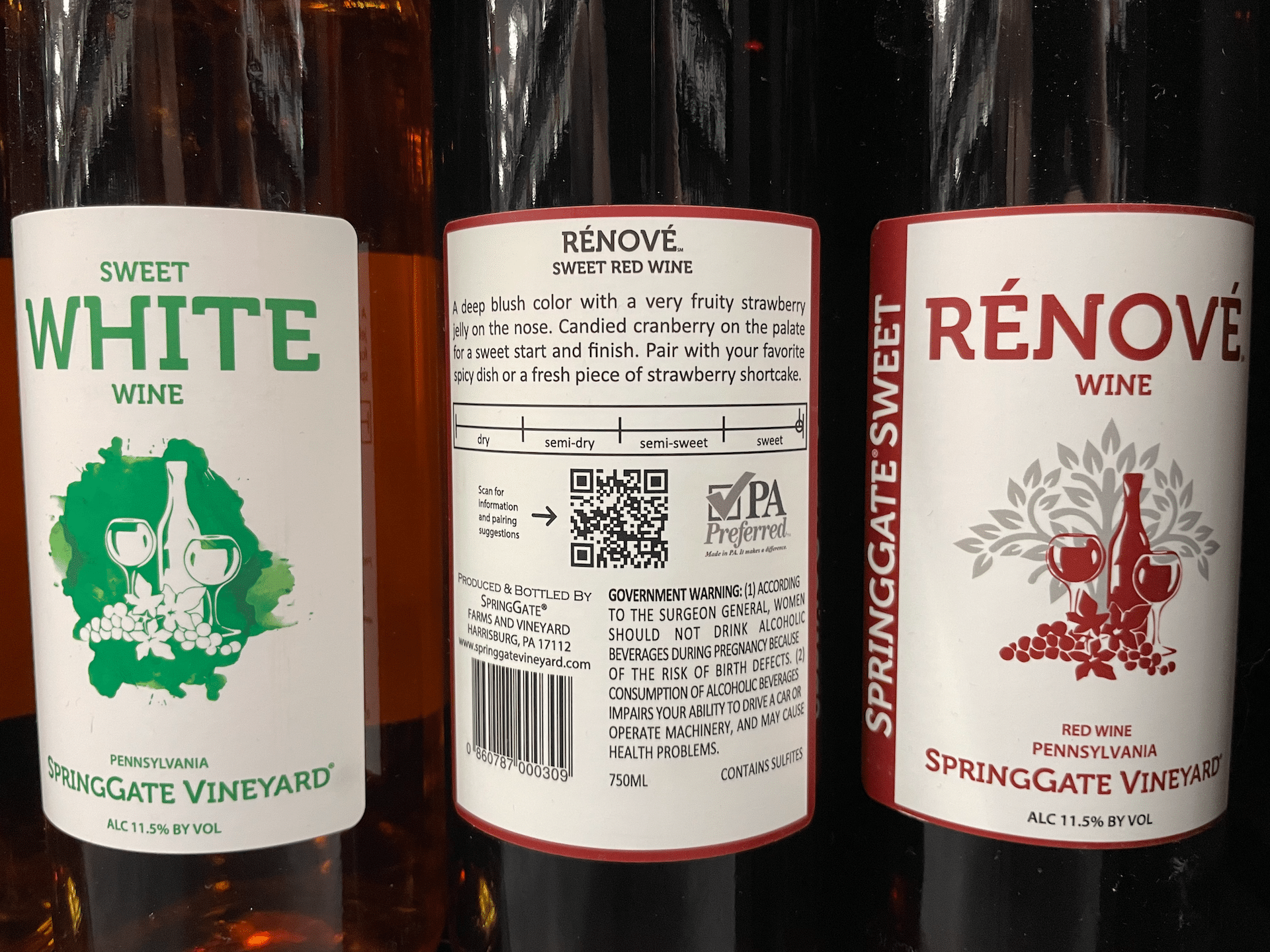

Sulfites: If a wine contains more than 10 parts per million (ppm) of sulfur dioxide, a common preservative, it must state so on the label. You’ll usually see “Contains Sulfites” written, which is particularly important for those with allergies.

Government Warning: All wine bottles must state the following:

GOVERNMENT WARNING: (1) According to the Surgeon General, women should not drink alcoholic beverages during pregnancy because of the risk of birth defects. (2) Consumption of alcoholic beverages impairs your ability to drive a car or operate machinery, and may cause health problems.

For standard wine bottles, it must be of a 2 millimeter-sized font, contrasting color to the background, and separate from other label elements.

Producer: As previously mentioned, domestic wines must include the producer name. If it differs from the brand, you’ll usually find it on the back of the bottle. Imported wines must also include producer address.

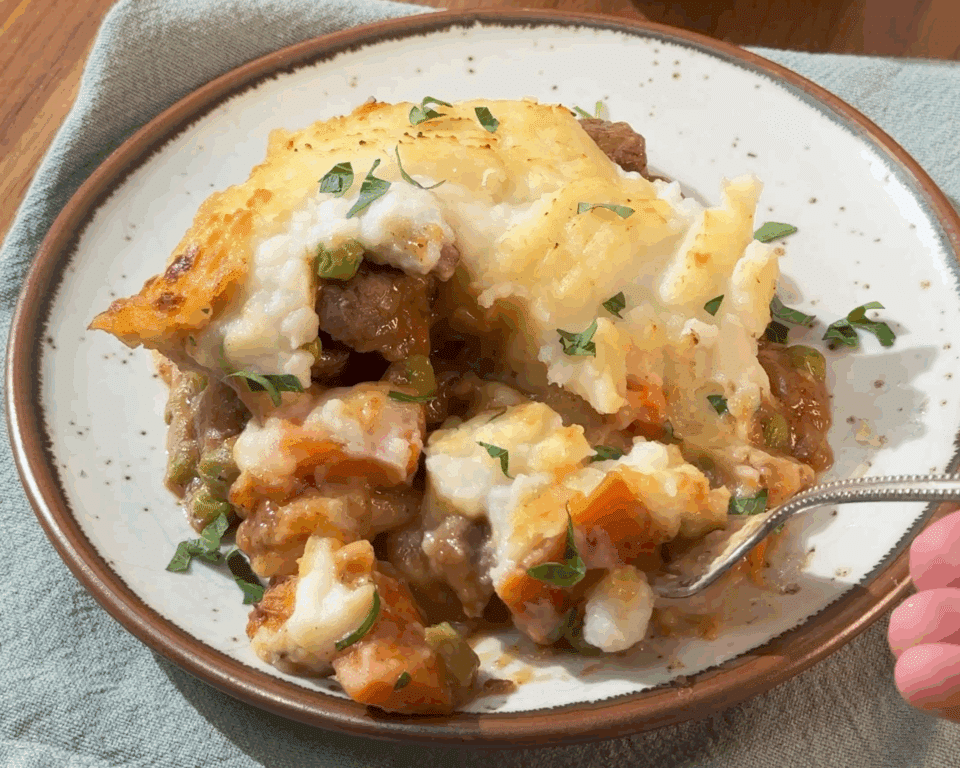

Added Information: Some wineries include extra information on the back label, including grape percentages, tasting notes and food pairings.

If a varietal is listed on the front of the bottle, like Cabernet Franc, the remaining 25% or less of the wine’s composition can be described.

Optional tasting notes help orient you to the wine’s aromas, flavors, body, texture and finish, while pairing suggestions help you understand what types of foods are mutually enhancing with the wine.

Final Notes

While wine labels are loaded with information, Schorran sees room for at least one more data point: residual sugar. It’s something that tasting room visitors often ask her about, yet remains unreported. Some consumers prefer wines with less residual sugar, or simply want to know how much they’re consuming. Schorran says, “A lot of the market in PA is still wines that are finished with some residual sugar and, unless the producer opts to put a scale or number on their label, it’s something you have to seek out and answer for yourself.”

Wine labels are an increasingly valuable marketing tool for wineries looking to stand out from the competition. “When my parents started the winery 30 years ago, there were only something like 2,000 wineries in the U.S.,” says Schorran. “Now there’s over 11,000.”

Galen Glen last updated its primary label in 2016. “We were getting our wine on supermarket shelves and really wanted a label that was going to pop, because that was a new place for us to sell.” Coming up soon, the Erin Elizabeth line will release a new label for its first rosé sparkling wine.

The look and feel of labels continues to evolve. “We’ve definitely gone away from the very traditional-looking, black and white sketches of the chateau,” Schonner says. “Brighter, more vibrant colors, bold features and anything to draw you to that bottle on the shelf is what’s popular right now.”

To try the award-winning wines of Galen Glen and examine its beautiful labels up-close, visit its stunning Lehigh Valley tasting room and vineyards or order its wines online. 255 Winter Mountain Dr., Andreas; (570) 386-3682.

The PA Vines & Wines series was created in collaboration with the Pennsylvania Wine Association.

The Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) is a trade association that markets and advocates for the limited licensed wineries in Pennsylvania.

- Feature and Galen Glen photos: Galen Glen

- Other photos: Leigh Green