You open a bottle of wine, pour a glass, swirl and take a sip. What do you taste? Maybe there are notes of green apple and honeysuckle, or perhaps some black cherry flavor with hints of tobacco. Or, maybe it just tastes delicious. Knowing how to identify and describe a wine’s key features is a unique skill set with a significant learning curve. But, it’s something that any wine lover can achieve with time, practice and guidance.

Noelle Allen, co-owner of Philly Wine and a Wine & Spirit Education Trust (WSET) Certified Educator, works with people of all levels to improve their palates, wine knowledge and blind tasting skills. She shared her method for breaking down and analyzing wine, sip by sip, to better understand its characteristics and journey to your wine glass.

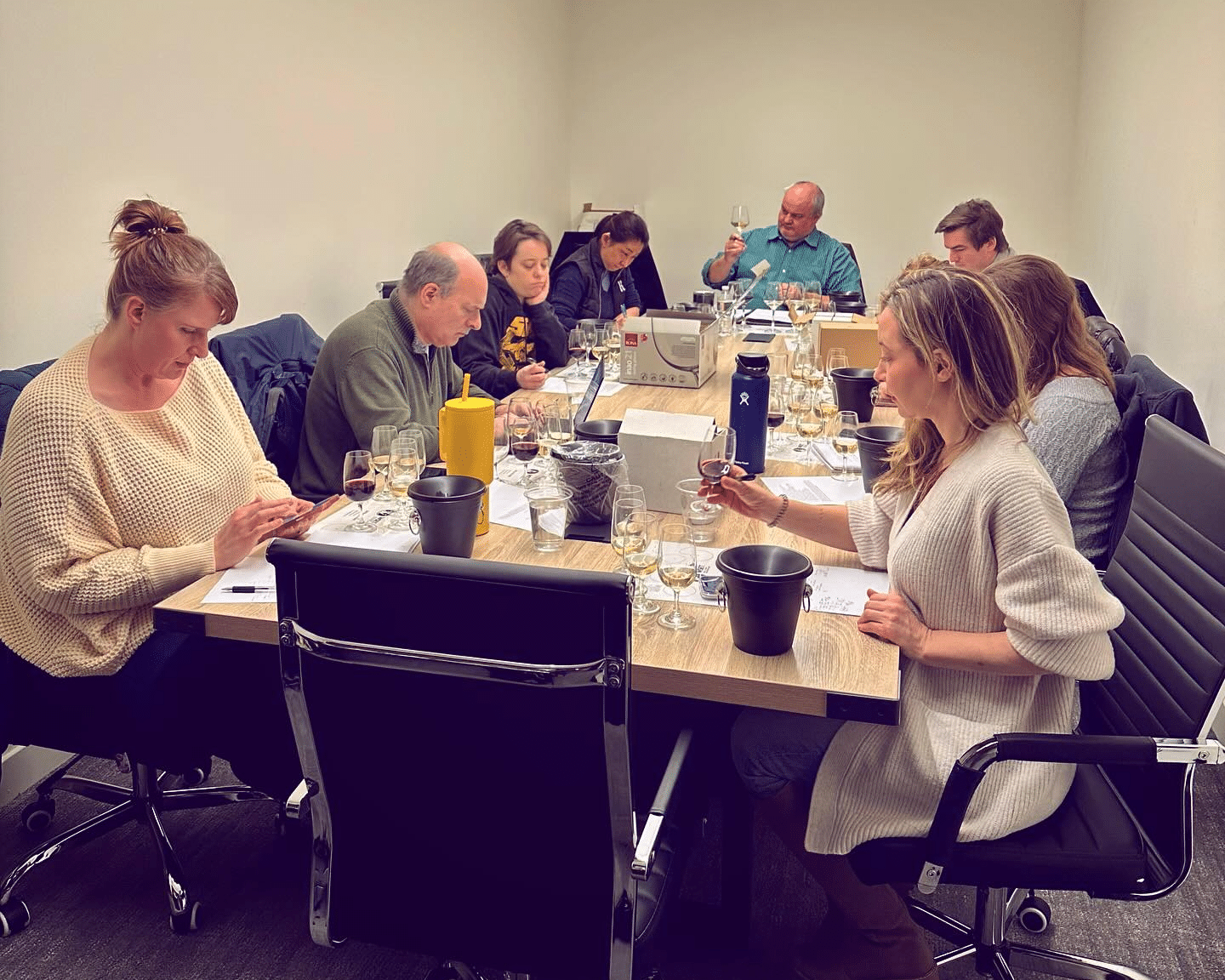

Noelle Allen, far right, with fellow professionals at Fitler Club

Setting Up a Blind Tasting

Blind tasting wine is one of the best ways to expand your wine knowledge and improve your palate. Allen says, “I always tell my students that there’s a lot of information in a glass of wine, and you’re going to learn to decipher that information through tasting. Blind tasting, in particular, puts a little more pressure on the taster to break the wine apart into its different components.”

Allen suggests doing blind tastings with others. In particular, connecting with someone who knows a little (or a lot) more about wine than you do offers the best educational experience. If that’s not possible, Allen suggests reading the wine’s text sheet as a point of reference. The text sheet is essentially a taster’s cheat code, providing the wine’s origin, variety, AVB, acidity, pH, sugar, tannins, oak and lots of sensory information. “As you become familiar with the sensations being correlated to the descriptors in terms of flavor, then move on to the winemaking technique. If you have something very high acid and floral with a lot of citrus fruit, the text sheet will give you words to describe that, like lemon or orange, certain white flowers and words like crisp, unoaked or fruit-forward.”

You’ll also need to determine how many wines to taste, and which ones. Allen says, “I would recommend starting with four glasses; maybe two whites and two reds with totally different profiles.” This will provide you with context and contrasting points, allowing certain elements of the wine to stand out.

Allen’s recommendations, along with our Pennsylvania wine version, go like this:

- High acid white: Try Sauvignon blanc from New Zealand or this one from Armstrong Valley Vineyard & Winery.

- Heavier, oaked white: Try Chardonnay from Napa, CA or Armstrong’s Oaked Chardonnay.

- Light, juicy red: Try Gamay from France, like DeBouef Boujalais or a light, unoaked Chambourcin like this one from Galen Glen.

- “Bigger” red: Try Cabernet Sauvignon from CA, Rioja Reserva from Spain, Shiraz from Australia or Petit Verdot from PA wineries like Karamoor or Va La Vineyards.

In general, Allen suggests starting with a lighter wine and then moving to a heavier one. “It’s really going to help you isolate the acid, notice higher alcohol, oak or lack of oak, and feel the tannins, length and grip,” she says. “Wine gets more specific with context.”

A Blind Tasting System

A wine’s appearance is the first entry point to understanding more about it. Allen says, “When you have a glass of wine in front of you, before you’ve even smelled it, you already know a lot about it just by looking at it. For example, a deeper color gives an indication of skin contact, oak and age. The brilliance of the wine tells you about acid. Different shades of red and white indicate certain grapes.”

Appearance

The appearance of a wine includes a variety of telling aspects, including color hue and intensity, clarity and brightness, viscosity (aka “legs”) and bubbles.

Typically, appearance ranges from pale to deep and spans a particular color spectrum. Lighter, paler colors in hues of lemon, pink, purple or ruby indicate a young wine, often a crisp acidic white or a fruity, low tannin red. Golden whites, orange-y rosés and garnet or tawny reds are often more mature, fuller bodied and possibly oak aged wines.

You’ll notice deeper reds hues in from wines made with thicker skinned grapes, like Cabernet Sauvignon. “You can start to eliminate some grapes based on what you’re seeing,” Allen explains. “If you see a really deep, thick red wine, you can probably eliminate Grenache or Pinot Noir because those are thinner skinned grapes that won’t give that much color.”

Most stable, quality wines are clear and bright. Sometimes, you’ll see a hazy, cloudy wine, which indicates either “natural,” unfiltered production or flaws like oxidation and spoilage.

The viscosity of a wine is, simply speaking, its thickness. This is closely related to its body, which we describe with words like “light,” “medium” and “full-bodied.” You can see this in the wine’s appearance by gently swirling it in the glass. A viscous (high viscosity) wine will cling to the sides of the glass while sliding down, creating what are called ‘legs” or “tears.” A less viscous, more fluid wine will just slide right back down into the glass.

Finally, bubbles provide clues about a sparkling wine’s production and taste. A gentle stream of fine, little bubbles often indicates a high quality wine made in the traditional method. Larger, faster bubbles result from tank fermentation for more casual sparkling styles.

The Nose Knows

When smelling a wine, pay attention to its intensity and aroma. Those elements reveal a great deal about it.

A light, delicate nose may indicate a younger wine, one with less alcohol and/or a cool climate origin. A powerful nose suggests warmer climate grapes, higher alcohol, possible oak aging and, generally, a fuller-bodied wine.

The nose of a wine introduces you to its primary, secondary and tertiary characteristics. Primary characteristics are from the grape’s fermentation and might be fruity, floral, herbal or spicy. Secondary characteristics come from the winemaking process. “This is about human intervention,” explains Allen. “That would include things like oak or lees aging and malolactic conversion.” The resulting nose may have vanilla and spice, a bready or nutty nose or creamy, buttery notes. Finally, there are (sometimes) tertiary characteristics. “They may not always exist, because these are bottle age notes. If the wine sits in the bottle for a while, chemical compounds start to change some of the flavors. Maybe something that began as lemon in its youth has turned to ginger in its older age,” Allen says. As fruitiness gives way to new compounds over time, older wines may develop such aromas as wet leaves, truffles, dried apricots, butterscotch and even petrol.

Tasting the Wine

Allen and Business Expo guests discussing wine at Fitler Club.

After examining and sniffing the wine, you’re equipped with foundational insight into its character ready for the actual tasting. As you begin sipping, follow this list of categories to help you further understand the wine in your glass:

Sweetness: Start with considering the sweetness — or sugar level — of the wine. A sweet wine will taste obviously sweet, with syrupy, sugary taste and honey, peach, berry or tropical fruit flavors and a soft feel. A dry wine may taste “lighter” in your mouth with crisp, acidic or tart notes, higher tannin (a drying sensation or bitterness) and dark fruits, citrus, oak, herbal or spice flavors.

Acidity: Acidity in wine balances sweetness and alcohol while adding complexity and freshness. A high acid wine will taste juicy, zesty, lively or bright. It might cause you to salivate. A low acid wine can taste smooth, soft, creamy or flat. Without enough acid, a wine can taste listless or “flabby.”

Tannin: As mentioned, tannin levels create a drying or puckering sensation. This is called “grip.” They may also have more depth, firmness or structure, like there’s a backbone anchoring the wine.

Alcohol Level: Alcohol is usually related to the weight of the wine. A low alcohol wine will taste light, delicate and perhaps more refreshing, though hopefully not watery or thin. A high alcohol wine will taste full-bodied, bold and rich. Sometimes the alcohol mimics fruit, creating a ripe “jammy” profile. If not balanced well, a high alcohol wine can taste “hot,” with a burning or harsh sensation.

Body: This is the weight on your palate, and requires attention to the mouthfeel. Is it thin and airy? That’s a light-bodied wine. Rich and dense? It is full-bodied.

Flavor Intensity: The intensity of a wine’s flavor might be light, pronounced or somewhere in between. Light intensity wines might be subtle and delicate, whereas pronounced wines have bold and obvious flavor, which can result from riper grapes, oak aging, lees contact and higher alcohol.

Flavor Characteristics: Create your own tasting notes by describing the primary, secondary and tertiary characteristics of the wine. The sky is the limit here, as you consider fruit, floral, herbal and spice notes as well as the winemaking techniques and aged qualities of the wine.

Finish: Finally, how long does the wine last on your palate? Does it linger and slowly fall off or vanish right away?

It’s also important to consider the quality of the wine, which is how well you think it was produced, technically, and how well it expresses the grape(s) and terroir.

Exercising Your Palate

Allen suggests a couple of exercises for honing your tasting palate. The first helps you to isolate tannins and acid, which can be a challenge. “They create sensations in your mouth that can masque each other,” Allen says. “So, for isolating acid, take two sips of wine. The higher acid can attack the palate, so the second sip helps to calibrate. Then, after you swallow the wine, hold your head down, lips closed, and see how much saliva begins to pool. It’s kind of gross, but that will give you an indication of higher or lower acid.”

“Acid is a wetter sensation,” she explains. Tannin is dry. So, when you take that second sip, see how much drying sensation occurs. If you’re feeling it only around the gums, that is a lower tannin. If a drying sensation makes it about midway back, that’s medium tannin and if you’re dry all the way in the back of your mouth, that is a higher tannin wine.”

For times when you’re not drinking wine, but would still like to practice, Allen suggests smelling thing around you. “Get the spices out of your spice rack and do a blind smell test, or try it with fruit, flowers or wood. If you want to move into tertiary notes, smell mushrooms, wet leaves, wet stone, chalk and slate. Start to lock in these sensations and, when you’re tasting wine, you’ll find you’re more easily able to retrieve that memory and describe it.”

While the world of wine tasting is exciting, with endless information to learn, Allen suggests that people take it slow. “This is not a practice you master overnight. Blind tasting puts a lot of pressure on you, and that pressure can change your palate and your chemical balance. ‘Go slow’ is such hard advice to take because we all want to know things quickly and show off these skills. But, go slowly, be methodic, read the text sheets and practice, practice practice.”

Wine education at Philly Wine

To learn more about all-things-wine, check out Philly Wine, which holds in-person classes at Fitler Club, 24 S. 24th St., Philadelphia, and stay in the loop by following Philly Wine on Facebook and Instagram.

The PA Vines & Wines series was created in collaboration with the Pennsylvania Wine Association.

The Pennsylvania Winery Association (PWA) is a trade association that markets and advocates for the limited licensed wineries in Pennsylvania.

- Feature photo: Bigstock

- Photos with Noelle Allen and Philly Wine: Philly Wine

- All other photos: Bigstock