Catering chefs are virtuosos. They create gourmet experiences on massive scales from behind the scenes, all while juggling dizzying logistics. Transportation, equipment, menus, and timing are all in flux, and expectations are high. For the Black pioneers in this trade, social and economic conditions only exacerbated the pressures, yet they created and grew this industry in style.

Catering answers the persistent call for fine, prepared food at large functions. Whether catering chefs are stationed at the event venues or cook offsite, they create custom meals as casual or fancy as you wish. The growing U.S. catering market should reach about $125B by 2032, with Pennsylvania boasting a healthy and diverse sector of wedding, corporate, social and production catering businesses. It all started nearly 250 years ago with the work and innovation of Black entrepreneurs in Philadelphia, who both established and fine-tuned the trade over time.

During the winter of 1777-1778, British troops in Philadelphia and Continental troops in Valley Forge were in gridlock. Though the Declaration of Independence had been signed, the British occupied Philadelphia, hoping to squelch the country’s burgeoning morale and lure George Washington and his troops out of Valley Forge and into full scale battle. At that time, Philadelphia’s Black community was growing, with approximately 1,000 free Black citizens and a dwindling enslaved population of about 400 people. Among the free Black community was Caesar Cranshell, who was about to make history.

During the nine months of British occupation, the Black community pivoted, often working as laborers, chefs and servants for the temporary British population that had taken over some of the city’s finest homes. As occupation grew untenable and defeat inevitable due to logistics and France’s entry into the war, British General Howe decided to resign and abandon the takeover altogether. But not without an epic party first.

The farewell ball for General Howe took place on May 18, 1787. Called “Meschianza,” the fête was an extravagant mix of military parade, medieval cosplay, fine dining and fireworks for about 400 people. The banquet dinner was orchestrated by Caesar Cranshell, who led the cooking and service, much of which was handled by enslaved men. It was the first major catered event in the United States and a remarkable culinary feat.

Though we don’t know the specifics of the menu, it’s likely that Cranshell prepared the typical formal fare of the time, including items like roasted mutton, beef or chicken, local produce, wild game, oysters, savory pies and puddings. He was not only catering to a massive, flamboyant crowd, but for British foks whose relatively foreign tastes and expectations could have only added to the challenges. Though ostentatious and contentious, the ball was a success and quietly launched the American catering industry.

Savory meat pie as Cranshell may have prepared

A few years later, in March of 1780, Pennsylvania passed the Gradual Abolition Act, the country’s first extensive legislative act to abolish slavery. Although it did not immediately free any enslaved people, it ensured that no one would be born into lifelong bondage anymore. Philadelphia became a safe haven and mecca for fugitive and free Black Americans, alike, as well as refugees from Haiti following the Haitian Revolution. The city’s free Black population exploded, growing to over 12,000 by 1820, setting the stage for further innovation of its culinary landscape.

It was during this time that Robert Bogle appeared on the scene. Formerly enslaved, Bogle eventually came to live in Philadelphia’s South Ward as a free man, though the details of that transition are unknown. He’s widely recognized as the “father of American catering” for transforming event services into a model that paved the way for African American catering businesses for over a century.

Bogle opened his “posh eatery” in 1912 at 46 South 8th Street in what’s now Center City, where he served the city’s white elite. Bogle took the role of public butler and expanded it, offering fine food, drink and staff for funerals, banquets, balls, christenings and high society weddings. His keen social acumen allowed him to network fluidly and purposefully, gaining the business and accolades of prominent individuals like banker Nicholas Biddle, who even penned a poem about him. “Thy reign begins before our earliest breath, nor ceases with the hour of death,” Biddle wrote of Bogle’s influence.

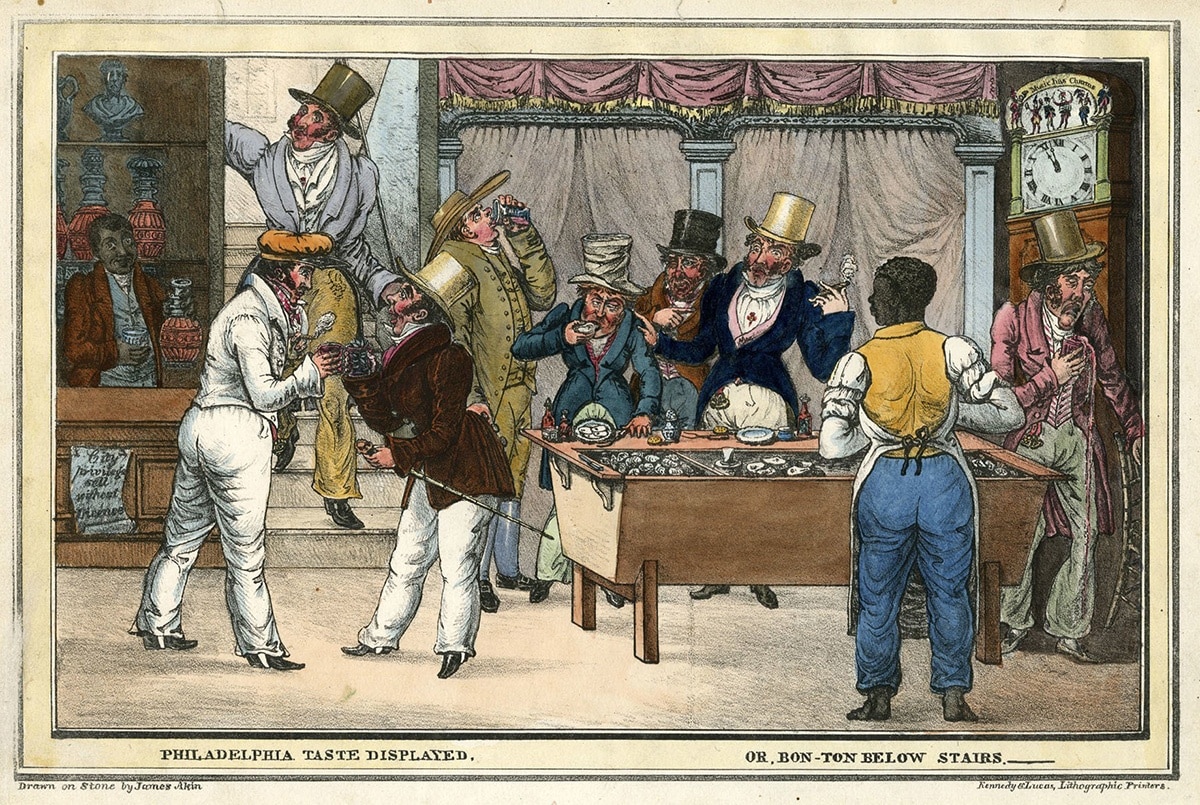

A Philadelphia oyster cellar circa 1930 by James Akin

Bogle excelled with meat pies and terrapin soup, for which he was known, and likely served a variety of popular delicacies like oysters and roasted meat. Bogle’s terrapin (or, turtle) soup would have been made with meat of diamond-back terrapin from the Delaware or Chesapeake bays stewed with butter and flower, seasoned with herbs and spices like cayenne and thickened with egg yolks and cream. You can find a similar soups made with snapping turtle meat in the Philadelphia region today at places like Oyster House, not far from Bogle’s original kitchen site.

Turtle soup like Bogle prepared

Bogle’s legacy lived on through the caterers who followed in his footsteps, many of whom he trained himself. Their catering dynasties built upon his model and ruled Philadelphia’s fine dining scene in the mid 1800s. One such caterer was Peter Augustin, Bogle’s successor. A Haitian immigrant, Augustin took over Bogle’s business in 1818 and assumed his central, influential and high-pressure role. Augustin operated his business on 11th Street and expanded the catering model to include end-to-end service for events. He provided set up, rentals of fine china, linens, tables and chairs, tear down and a trained team of chefs, waiters and butlers who handled it all seamlessly. W.E.B. DuBois wrote of him, “It was the Augustin establishment that made Philadelphia catering famous all over the country.”

Croquettes like those Augustin made famous

Augustin developed a recipe for chicken croquettes that Philadelphia history lovers still make today. After his death, Augustin’s wife Mary Francis Augustin took over the business with their son James, and it continued from there. You can learn more about the family’s profound impact in this documentary. Similarly, the Prosser family operated a popular oyster house on Market Street under two generations of ownerships around the same time.

High society’s appetite for exceptional catering services grew, providing ongoing demand for the expanding network of African American hospitality professionals. The industry became an economic system that thrived behind the scenes, offered Black Americans a skilled and lucrative path and a professional space somewhat sheltered from the predominantly racist public systems and attitudes of the time. This network was strengthened by the Colored Conventions Movement, a series of large scale meetings for Black leaders to gather, commune and plan, paving the way for organizations like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

![February 6, 1869 Illustration from Harper's Weekly of the Colored National Labor Union convention in Washington, D.C. Store Web page states: "from Harper's Weekly magazine with 6 x 9 [inch] wood-engraved illustration of the The National Colored Convention in Session at Washington, D.C."](https://www.paeats.org/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/The-National-Colored-Convention-in-session-at-Washington-D.C.-sketched-by-Theo.-R.-Davis.png)

1869 illustration from Harper’s Weekly of the Colored National Labor Union convention in Washington, D.C.

Dorsey was born enslaved before escaping to Philadelphia, getting recaptured, and then purchasing his freedom with the help of abolitionists to stay in Philadelphia. He was known for his refined taste and dominant personality and developed a menu including filet de boeouf-pique, terrapin, deviled crabs, chicken croquettes and ladyfingers. He earned enough to buy real estate and rent to white tenants, a rarity for the era.

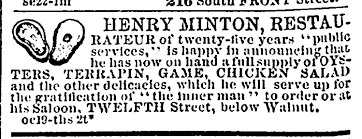

Jones, too, was born into slavery before making his way from Virginia to Pennsylvania, where he established his successful catering business. In his obituary, the Philadelphia Inquirer, 1875 edition, described him as a “careful, attentive, honest, and skillful” man. Henry Minton operated his successful restaurant and catering business near Jones’ home. In The Condition, Elevation, Emigration and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States (1852), Martin R. Delany wrote:

The tables of Mr. Henry Minton are continually laden with the most choice offerings to epicures, and the saloon during certain hours of the day, presents the appearance of a bee hive, such is the stir, din, and buz, among the throng of Chestnut street gentlemen, who flock in there to pay tribute at the shire of bountifulness. Mr. Minton has acquired a notoriety, even in that proud city, which makes his house one of the most popular resorts.

An 1860 ad announcing the relocation of Henry Minton’s restaurant.

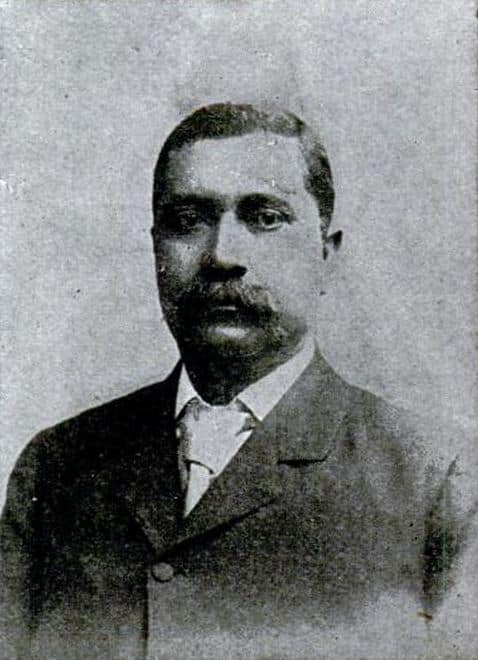

John S. Trower, who became one of the nation’s wealthiest African American men by his death in 1911, established a restaurant and then a catering company in Germantown, an upscale area of the city. Trower had one of the finest catering sites in the country, with three floors of reception and dining areas, offices, a delivery department, an ice cream plant and an in-house bakery. He employed all African American men and women in his office, and had a staff of 20 for the culinary, ice cream, baking and delivery teams.

John S. Trower

Ultimately, the lineages and networks of these pioneers dwindled to just one family: the Dutrieuelles. Society’s changing culinary habits and preferences, increased middle class access to catering, fierce competition, copying and absorption by other groups, and economic changes all contributed to the downturn of the industry. The Dutrieuelle catering line started with Pierre Albert Dutrieuille in 1873, who married into the Baptiste-Augustin family and passed the business on to his son, Albert. Albert had four daughters, who did not carry on the business. It closed when he retired in 1967, effectively ending the dynasty of the original African American caterers.

Nonetheless, the legacy of these early entrepreneurs endures. Catering is foundational to America’s dining experience, and forever intertwined with our celebrations and most special occasions. The next time we tuck into a catered work lunch or enjoy the elegance of a fine, multi-course meal at a wedding, let’s take a moment to remember the people who started it all.

If you’d like to support modern Black-owned food businesses in Pennsylvania, check out these bakeries, cafes, restaurants and – yes – catering companies in southeastern PA, the Lehigh Valley & NEPA and central and western PA.

- Feature, croquette photos: Canva

- The Meschianza from Century Illustrated, Volume 12, James Akin art, Harper's Weekly image, Minton advertisement, Trower photo: Public Domain

- Meat pie, chef plating salads photos: Bigstock

- Turtle soup: Pexels